Jesús Lugo

There is, without a doubt, something obsessive in the work of Jesús Lugo. How else can one explain that, within the limits imposed by the canvas, most of his paintings are animated by a nearly infinite multitude of such diverse characters, with different expressions and attitudes?.

Plenitudes and voids in the work of Jesús Lugo

by Esteban García Brosseau (june, 2021)

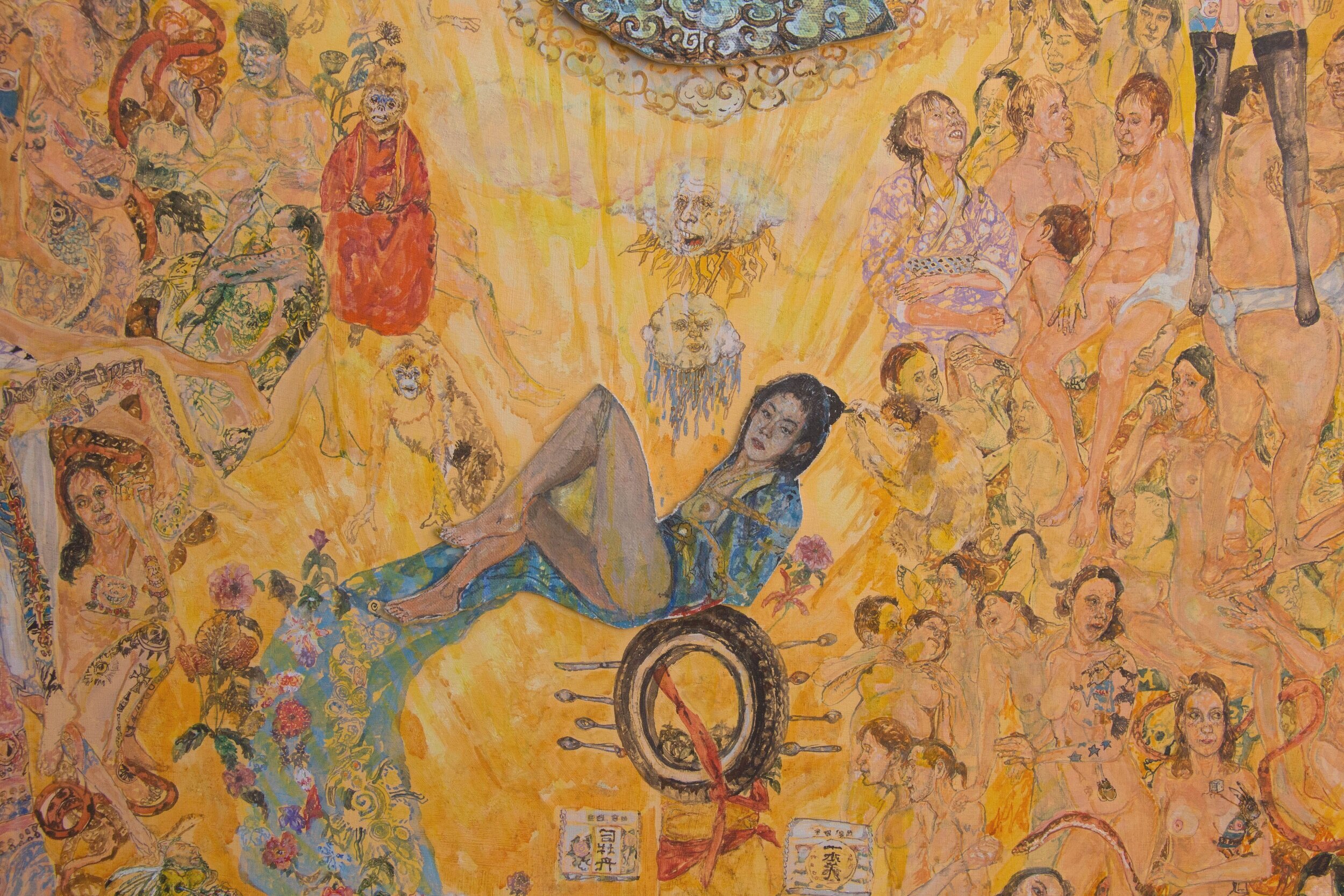

There is no doubt about it: there is something obsessive about the work of Jesús Lugo. If not, how could we explain the almost infinite number (limited only by the frame of the painting) of varied characters that animate most of his canvases? By seeing them, one tends to ask oneself what is the reason for these crowds that, seen from afar, could almost evoke the shapes of an abstract painting due to their composition and color? We are, however, standing in front of a figurative work, which brings us naturally to look attentively at each of the individuals that are here portrayed collectively, as it happens with the paintings of Bosch, Breughel and, perhaps even more, with the descendants of the latter, Jan Brueghel the Elder and the Younger. Thus, the affinity of Lugo with Flemish painters, becomes evident from the first moment, even if he is himself a painter of the 21st century.

The characters which are thus portrayed by Lugo are diverse. Sometimes it is just common people: a man here, a woman there, a young lady with her yellow sweatshirt farther away ; but, beside them, we may see simultaneously a prostitute in garters, a couple making love without any pudor, naked women in more or less obscene positions who sometimes reign at the center of the composition as tantric goddesses….The canvass, from a collective portrait, would thus tend to become an orgy, if it wasn’t for the solitude in which each of the characters thus portrayed seems to be confined, which makes that tendency impossible: all of this characters, who are depicted by Lugo with the precision that his predilection for drawing allows him, do not seem to establish any bonds between them, or very few at least

Instead, they seem to be imprisoned within their own singularity: the crowds that are shown to us by Lugo do not seem to be connected to each other by sharing a common cause (a party, a celebration, a manifestation), but seem caught instead in the net of solitudes woven by civilizations; not only ours, but also past ones, whether Prehispanic, African or Asian, as can be seen by the multiple subjects of this work, in which the spectator sees successively passing before his eyes Buddhist Asia (with Buda being tempted, as was Saint Anthony, by the demon Mara and his hosts of women), the Nymphéas (and Nymphs) of Monet’s garden at Giverny, a great Mexica plaza that recalls somehow the Prehispanic Mexico of the muralists (although including a European queen that dominates the scene with a couple of female courtesans pornographically submitted at her feet as well as a viceregal gentleman who wanders in the middle of the scene as in Villalpando’s La Plaza Mayor de México), modern cities similar to Mexico City as it was depicted by O’Gorman, but in which an anachronism always appear here and there, as to show that all periods are equivalent. In general, by passing from one painting to the other we may see appearing, in the middle of a modern crowd, a medieval peasant woman, a noble lady from the 16th century, Francis I, a Renaissance Pope, a bourgeois from the 17th or the 18th century, all of which, remind us that Lugo’s work is mainly a dialogue with the history of art, in which his own preferences predominate.

Lugo’s work could seem completely devoted to the idea of art for art’s sake, to the point that it sometimes reminds us, by its multiple artistic references, of the kuntkammern represented by Jan Brueghel the Younger, Teniers the Younger, and other Flemish painters. But precisely because it puts the whole of humanity in front of our eyes, it suddenly becomes, without any fanfares nor coarse allusions, a social reflection, as unvoluntary as it may be. While Lugo’s work constitutes a vast reflection on the meaning of art for itself, as an historical continuum from which every artist is nourished, it contains, at the same time, a philosophical statement on the meaning of existence: when seeing this multitudes of solitary beings who travel across the eras filling the canvass as humanity has filled the world and its history, one is confronted simultaneously to the idea of absence.

But absence of what, one may ask. If what we were seeing was the central panel of The garden of earthly delights it would be easy to evoke the absence of God. In Bosch, just as much as in Lugo, humanity, which should be enjoying the plenitude to which it was invited, seems, on the contrary to be erring, suspended in the nothingness of reality, which only seems to function as a background. But, not knowing what is the meaning that a contemporary painter may give to God, or simply to the sacred, in this era of void, one may ask to oneself at which absence does Lugo’s is aiming when saturating his canvasses with human beings of all kinds, but without making them really interact with one another? Could it be that he wants to reveal that state of orphanhood that Octavio Paz attributed to the Mexicans in his Labyrinth of Solitude? Lugo’s painting isn’t nationalistic-as he himself ascertains-, and it aims at universality; however, the same could be said of Paz when he writes: “Our solitude has the same roots as religious feeling. It is a form of orphanhood, an obscure awareness that we have been torn from the All and an ardent search: a flight and a return, an effort to re-establish the bonds that unite us with the universe”. 1 Thus, Lugo’s work, by making us participate of the mere aesthetical delight of the works of art of all times,- including his own, of course-, seems to bring us to witness, at the same time, the painful and often absurd mystery of existence which, across the centuries, as collectivities and individuals, has founded the very essence of humanity.

_____________________________________

1 Octavio Paz, The Labyrinth of Solitude, trans. Lysander Kemp, Yara Milos and Rachel Phillips Belash (New York: Grove Press, 1985), 20