Armando Romero

Perhaps the more evident, the more adhoc with collective thinking, and its need for normativity, would be to think, that all of those who, like Armando Romero, modify the great works of art of the Renaissance and the Baroque, by adding to them stickers and other references to popular culture of every kind, desacralize them intentionally, because they openly despise the elitist culture from which they have originated.

Armando Romero: Hybrid imaginaries

by Esteban García Brosseau (May, 2022)

Perhaps the more evident, the more ad hoc with collective thinking, and its need for normativity, would be to think, that all of those who, like Armando Romero, modify the great works of art of the Renaissance and the Baroque, by adding to them stickers and other references to popular culture of every kind, desacralize them intentionally, because they openly despise the elitist culture from which they have originated. The role of this painters would be, therefore, to attack the status quo by utilizing art with “revolutionary” means, and by revendicating popular “aesthetics”, in opposition to the despicable will of “distinction”, - to recall Bourdieu-, by which the “non-popular” classes (by lack of a better expression) try to create a division between them and the “great majorities”, that according to this vision, they despise.

To charge against the symbols of high culture as the paintings of Rembrandt, Veronese, Breughel, or Velázquez, disfiguring them with graffiti or “maculating” them with images of the popular world, would be a sort of revenge by which the painter would throw to the face of those who look down on ordinary people, a well-deserved disdain, “from below”. Thus, the fact of supporting, for instance, the figures of Mexican wrestling (one thinks of Barthes and his interest for catch), who appeal, without doubt, to a wide sector of the population, would be a reaction and a response against those who believe they can distinguish them from the others (the supposed attitude of those who “se creen mucho”1 according to the Mexican expression) because they prefer to assist to the opera in Bellas Artes, than to go see Mexican wresting in the Arena México. The painter would thus become a sort of disciple or visual interpreter of Bourdieu’s sociology, and, in particular, of his famous book Distinction: A social critique of the concept of taste.

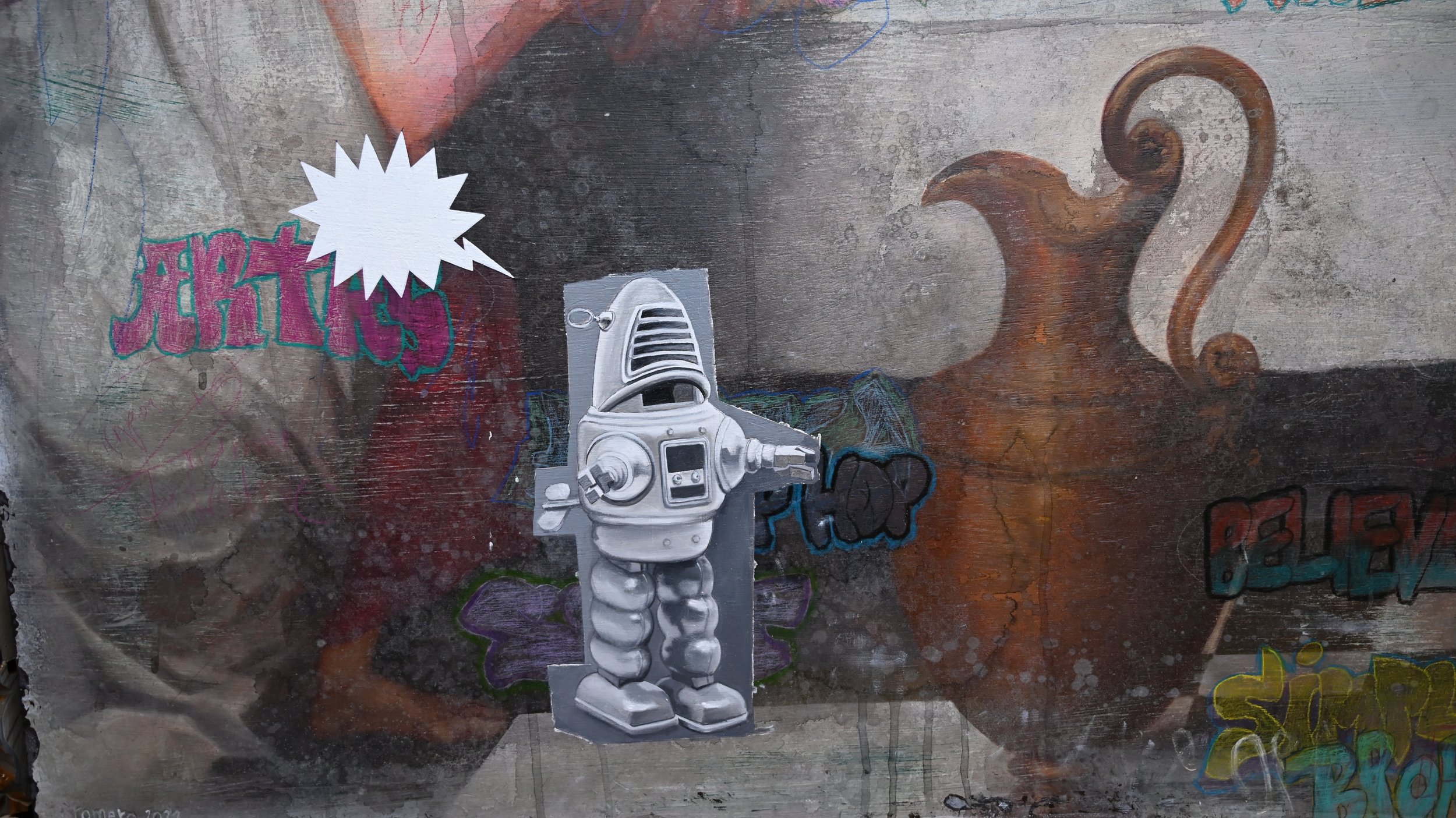

We could eventually recognize all those elements in the work of Armando Romero, as, indeed, he literally opposes to the great works of European painters that I’ve just mentioned figures that come from the popular world of comics, as those of the famous drawers Hanna and Barbera, who invaded the mental universe of Mexican kids from the sixties to, approximately, the seventies to the middle of the eighties. Thus, as elitist as may have been the education of those who gaze at the work of Romero, they might, at least, recognize some of these figures: Top cat, the emblematical robot Robinson YM-3-B-9 of the series “Lost in space”, the family of the Jetsons or the Pink Panther, the last being the most snobbish and intelligent of these figures, by the way, which is why, precisely, It was admitted even to the homes most hermetically closed to “mass culture”.

Of course, if it is true that many things have changed in the last decades, it is very likely that, on the contrary, those who haven’t received an artistic education of any kind, won’t feel much familiarity with many of the master works that Romero imitates, while they will immediately be appealed by the comic figures that he copies with such expertise, that they look as real stickers, to the extent, the artist tells us, that kids haves sometimes tried to detach them from the canvass. However, it also happens that some of his collectors, attracted, at first by the comics, end up being interested, in the biography of those masters that Romero imitates, which is, of course, very meaningful.

It happens that Armando Romero knows both worlds, because, even if the comes from a family of artists, his parents didn’t forbid him to watch television, and didn’t make a distinction between the “cultivated elites” and the popular classes, for whom they expressed a clear solidarity. Thus, the reproduction of works of art that he saw in his parents’ books, flowed in his mind along with the images he saw in the kids programming of Televisa, in free streaming and with no limitation. One could say, that much more than being defined by a will to desecrate, Romero’s painting simply appears to reproduce the two different visual universes that were his in his childhood, with the intention to unite them in one canvass.

Of course, it all goes much farther than this constatation, which, in fact, is not so anodyne as it could appear, as it makes us reflect on how important visuality can become in the construction of our identity, individual as well as collective. Thus, for instance, the insistent presence of comics opposed to the work of the great masters reveals the existence of a visual field imbedded in our minds, of which we probably will be unable to get rid of until the moment of our death.

If the last is interesting from the mere psychological point of view, it is also significative from a political perspective. Indeed, we cannot ignore that much of the comics that Romero opposes to the masterpieces of art history come from the American drawing studios of Hannah-Barbera, Walt Disney, etc. One could argue, indeed, that the invasion of the visual space of humanity by all those figures, corresponds to the American propagandistic will to create, after World War II a sort of visual hegemony that could substitute itself to the elitism of European culture, while addressing, above all, the common people who lived in the suburbs of north American cities, as it is made evident by series like the Flinstones or the Jetsons.

The fact that, in the present, a big part of humanity can recognize and even identify with these comics is a clear proof that there is an American “colonization of the imaginary” comparable to the European one, as it was described by Gruzinski for the 16th century in Mexico. Thus, Romero makes us think about the replacement of European visual culture by the American after World War II, which is not negligeable, even if this might not be a conscious intention of the artist. Perhaps because of this, it may be conceded that, in spite of being a painter in the strictest sense of the term, Romero could be considered as a “conceptual artist”, as some have affirmed: it thus would be a conceptual artist malgré lui.

Once arrived at this point, we can ask ourselves if that which Romero opposes to the paintings of the Renaissance and the Baroque is something truly “popular” because it is, in fact, a product of American “mass culture”, as we have seen. This certainly invalidates the hypothesis that would like to see in his painting a sort of “resistance from below” towards the values of high culture, unless we accept that, for a Mexican, to adopt without reserves the American “mass culture” would be a more dignifying action than to openly admire great European painting.

Additionally, when we know, for instance, the kind of artistic expertise needed to reproduce the great art pieces that Romero choses as the principal subject of his work, one doubts that his intention is simply to mock or despise them in any way, even when he decides to paint red noses on the solemn figures of a Dutch group portrait, for instance. We only imitate who we love, and we only love who we admire…What is then the intention of Armando Romero when he thus puts us in front of two visual fields as different while allowing himself to take away the solemnity of the more emblematic figures of art history?.

I believe, that far from wanting to alienate us from great painting, his intention is completely the opposite. Certainly, with his “vandalic” procedures, Romero demythifies those masterpieces, although not with the intention of destroying them, but, on the contrary, with that of bringing them closer to the visual and mental universe that, willingly or not, has become our own, in this era. Thus, he allows the great majorities to which we belong, to reappropriate the world of great European painting, which, without this type of visual and mental tricks, would perhaps have sunken forever in oblivion, particularly in Mexico.

To give an example of it, I will end with one of the predilect subjects of Romero: the group portraiture of Holland, which is, in itself, quite inaccessible when it comes to its meaning. That was the case for many years, even for European art historians, as Riegl pointed it out, in his famous book The group portraiture of Holland. 2 Thus, there are few people that, in front of such works of art, would be able to observe, with Riegl that the “serene, static, and yet deeply intense gazes of the figures make the viewer oblivious of anything that is at odds with the dominant mood”3 or that, while they form an entity in which each individual submits himself to the collectivity to which he belongs, they never lose their individual characteristics.

Now, when Romero superposes comic figures, graffiti, or red noses to all of this figures, he brings them closer and make them more familiar to us by taking away momentarily their solemnity. When he humanizes them in such way, he doesn’t do it as an adversary but as an ally that would have for them an immense tenderness and that, far from wanting to exclude them, would like, on the contrary to integrate them to our new world. What is paradoxical, and surprising about this procedure, is that, precisely because he thus brings those figures closer to us, we come to understand again the artistic expertise needed, for instance by a Rembrandt or a Franz Hals to immortalize their models in these attitudes, so characteristic of the group portraiture, in which pride and humility coexist in such a paradoxical manner. Thus Armando Romero, with his mischievous vandalism, but which appears, simultaneously, full of tenderness for the models of the great masters of art, and even more for the masters themselves, opens for us again the road that leads to the understanding of great painting, in all of its solemnity, even if, to do so, he has to entertain us and make us laugh a little, or a “little much”…we cannot escape our time.

__________________________________________

1 Alois Riegl, The group portraiture of Holland (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 1999).

2 Ibid, 64.